The Flint Crisis is Not Just About the Water. It’s About Poverty.

The Detroit News ran an editorial this week titled ‘Cooperate for Flint’s Future’, in which the board makes the case that Michigan and the country need to “stop shouting and pull together to help the people of Flint.” According to the article, “the problem in Flint has been recognized, and is being addressed.” But has the problem really been recognized, and is it being address?

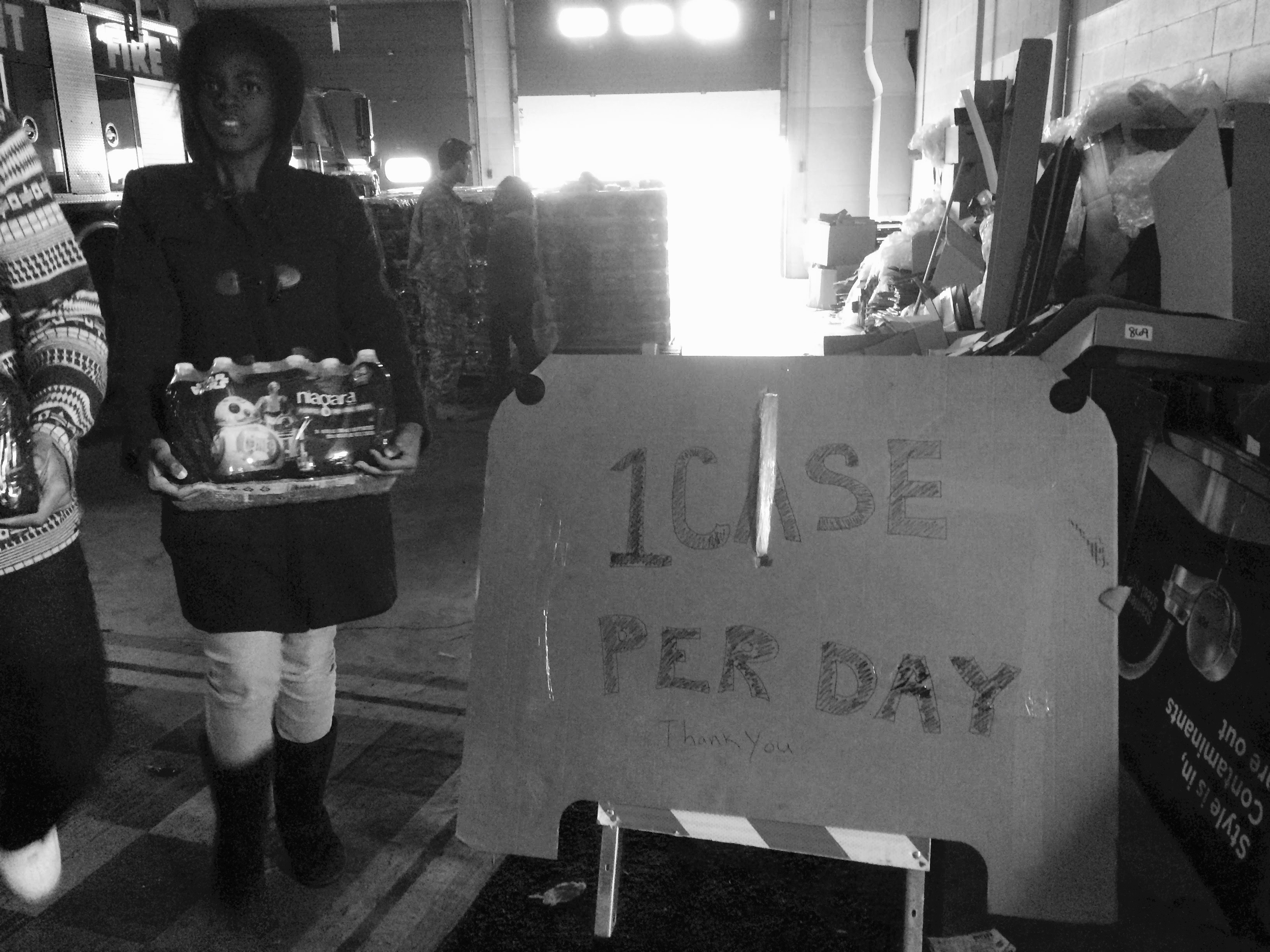

What those who bring cases of bottled water to Flint might be missing – however well-intentioned they might be – is that the real crisis here goes deeper than the dirty Flint River. Just as a band-aid won’t heal a bullet wound, fixing Flint (or metro Detroit’s) water crises without addressing the underlying problem of social and economic divestment won’t bring a bright future back to Michigan. At best it will delay the brunt of the pain until a new administration is elected/appointed, and at worst it will give us a false sense of resolution to yet another in a series of escalating social crises.

Neither can we solve this crisis by treating it like a natural disaster. Real natural disasters are treated like brief anomalies by relief agencies, where the goal is to restore the state of things before the disaster. Yet the crisis in Flint began long before the switch to dirty water, and even before the imposition of emergency management – two disasters stacked upon an already-disastrous situation. I’m reminded of the words overheard in Sandy-stricken New York or Katrina-stricken New Orleans: things weren’t OK here before the storm.

The first step in solving a problem is to understand it. The problem here is poverty: a lack of good-paying jobs, quality schools, and good housing. A city of 100,000 residents without a major grocery store. Poverty drives social alienation and despair, leading to distrust of, and disengagement from, the political system: only about 15% of adult potential voters in Flint and Detroit participated in recent years’ elections. (Certainly some of this disparity is from active voter disenfranchisement, not just disaffection.) Emergency management, which stripped what little remained of the power of the vote from residents by imposing unelected state leaders over them, accelerated this alienation – why should I vote if my vote doesn’t even count? When people can’t/don’t vote on issues that affect them, a vital safeguard against things like public utility poisoning is eliminated. To say that all Flint residents need is water filters is to miss the forest for the trees.

What do the people of Flint need? I toured Flint several times last year with the Detroit Water Brigade, a non-profit organization I co-founded in 2014 to aid and advocate on behalf of the thousands of Detroit residents without access to tap water in their homes and businesses. Local activists in Flint, faced with a population in deep poverty with some of the highest water bills in the state, had taken to doing what only now is the government doing: sharing water with people. The poor picked up donated water from local churches. A local trailer park within eyesight of the now-famous Flint water tower was disconnected from city water for non-payment, forcing its residents to pump water up from a well in a nearby cemetery. In a kind of cruel irony, some of the poorest residents of Flint may have been spared the worst effects of the lead-poisoning over these last few years because they were disconnected from the city system for non-payment. The crisis goes way back.

Governor Rick Snyder is right when he says “government failed you…by breaking the trust you placed in us,” but I wonder when he believes that failure began. It surely goes back decades, to the traitorous retreat of the auto industry from Michigan to cheap labor countries, accelerated by government policies like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and now the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). More recently, in a misguided effort to stem the hard effects of the global financial crisis, our state government tightened the belt of austerity and reenforced their policies with anti-democratic “emergency management” laws, rather than invest in our greatest asset: the people of Michigan. These failures preceded Governor Snyder, and they’ll follow after him unless we get serious about healing bullet wounds – and stopping the bleeding.

The Detroit News editorial board also erred in positing that “angry protests and mass demonstrations” have served their purpose, and now is not the time for “angry personal attacks and the politicization of this issue.” People are angry, but they’re also right and we must listen to them now more than ever. The fact that the Flint “issue” has become politicized is a positive sign that people recognize its importance, and it is pure cynicism to suggest that making the Flint water crisis a presidential issue won’t help fix it. We have seen the power of protest movements like Occupy Wall Street and #BlackLivesMatter to transform the agenda of both party’s presidential political debates, and to suggest this won’t help fix urgent issues like income inequality and police accountability is exactly the kind of defeatism that stifles political participation in our country. Let the protests and the vigorous debate ensue!

Flint’s water crisis should be seen as the final proof that government austerity policies have indisputably failed. It should also be the clarion call to a rising generation of American youth – diverse, intelligent and optimistic – that it is our time to step into the political fray. Just as newly-elected Flint Mayor Karen Weaver rode into office on a pledge to treat Flint’s crisis like the national emergency it is, we must think big and bold about the kind of government we want to rebuild in our shaken state. And that – more than any amount of bottled water or lead filters – will put us back on course to eliminating this shameful 21st century poverty.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.