On Free Education and Peter Cooper’s Gift of Self-Help

And wisest he in this whole wide land

Of hoarding till bent and gray;

For all you can hold in your cold dead hand

Is what you have given away.

-Joaquin Miller

I’m scaling the wide road leading up to the imposing Gothic arches of Greenwood Cemetery in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. All the sounds of the city are muted today, held in the droplets of drizzle that wrap the old cemetery in a blanket haze. Each tombstone reaches up from the soil and pierces this gently-falling blanket, an enduring human testament to a spirit long-removed from the Earth. A groundskeeper chats in thickly-Italian English to some passers-by about the recent upswing in suicide in Italy driven by a stalled economy and rising debt. I’m tempted to join the conversation, but I restrain myself and only ask politely:

“Do you know where Peter Cooper is?”

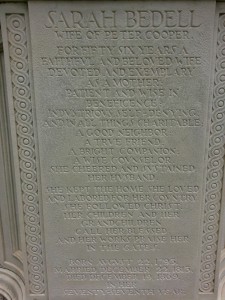

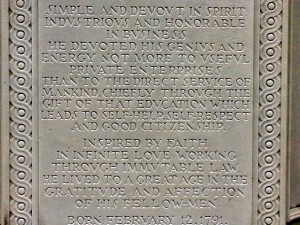

He directs me down a road called Central Avenue. Greenwood is a dense village of intersecting streets whose 560,000 permanent residents span the entire spectrum of human achievement. Many have been left with gaudy mausoleums and obelisks to their name, but not Peter. His gravestone, which he shares with his wife Sarah Beddell, is a simple and practical rectangular monument adorned with four epitaphs, one on each of its faces. It sits atop a grass island at the end of Central Avenue, and Cooper’s two children & their families – his son served as Mayor of New York City from 1879-1880 – surround Peter and Sarah.

What strikes me first about the epitaphs is their sheer humility, which even my own deep cynicism can’t refuse:

Simple and devout in spirit.

Industrious and honorable in business

And of his vast wealth and business empire – Cooper was one of the wealthiest men in New York in his time – his memorial says simply:

He devoted his genius and energy not more to useful private enterprises than to the direct service of mankind.

Chiefly through the gift of that education which leads to self-help, self-respect and good citizenship.

As I encircle the grave, I wonder what has become of this dichotomy between useful private enterprises and direct service of mankind that Cooper’s epitaph carves out. Written near the turn of the 20th century, at a time of expansive industrial growth and wild prosperity for the well-born few, the notion of direct service above profiteering must have seemed oddly virtuous. Over 100 years later, in a time of “disaster philanthropy” and “tax-exempt charitable donations”, it seems downright radical.

Cooper exhibits a remarkable self-restraint coupled with a deep sense of indebtedness to the society that built him. One gets the impression that his humble upbringing brought him to this point: he became apprentice at a young age to a carriage maker in lieu of a basic education, which was beyond his fiscal means. In his free time, he taught himself to read and write. He understood education to be the single most important maker of prosperity for the masses, and created an institution to embody that principle and carry it beyond his lifetime.

Shortly after his death, Otis M. Macmillan compared Cooper’s life to that of the still-living William Henry Vanderbilt, son of the railroad mogul Cornelius Vanderbilt, and an avid art collector living at the time in a palatial Fifth avenue mansion:

One was a philanthropist, the other is a miser.

One was benefactor, the other a stumbling block.

One did well; the other is constantly doing harm.

One helped his fellow-man – the other is injuring him.

Cooper wasn’t just a philanthropist, however, but an advocate against predatory usury and the debt system, a devout Universalist Unitarian, and a father who shunned excesses and reportedly returned his wife’s expensive horse carriage for a more modest one. Vanderbilt is enshrined in fiction history as Ayn Rand’s ambitious robber baron Nat Taggart. Cooper’s gentle face and sage white beard are his legacy.

The thing is – we need Peter Cooper more than ever today. America’s masses stand defenseless, knees buckling under the pounding weight of student loans. Youth look with dazed uncertainty into their financial futures, burdened by the poor job prospects and the empty leadership of their congressmen long-sold to monied special interests, to 21st-century Vanderbilts. Their yearning for Cooper’s promise of education for self-help and good citizenship has been rebranded by corporate spin-masters and their political minions as entitlement and handouts to cover up a heist of college endowments and public coffers that threatens the very future of accessible higher education for all.

Will another Peter Cooper appear to save the day? I’m not counting on it. Today’s philanthropists grew up in a time very different from Cooper’s apprentice days, in suburban homes with white picket fences. Absent from their worldview is the subtle, beautiful logic of self-help that Peter Cooper embodied and that drove him to establish a free school for qualified youth regardless of their race, religion, sex, wealth or social status. Today we ‘let the market handle it’. Collapse the dichotomy of direct service and useful private enterprise into one giant educational experiment to extract more wealth from the young to pay the old. Put the education of young America on a credit card and hand it to us later. Turn self-help to self-indebtedness.

The GI bill – which provided, among other things, free higher education to WWII servicemen – yielded the best return on investment this country has ever seen. Beyond the remarkable 7:1 monetary return in the form of enhanced economic activity, consumer spending and tax revenue, the GI bill produced 14 Nobel Prize winners, three Supreme Court justices, three presidents, 12 senators, 24 Pulitzer Prize winners, 238,000 teachers, 91,000 scientists, 67,000 doctors, 450,000 engineers, 240,000 accountants, 17,000 journalists, 22,000 dentists and millions of lawyers, nurses, artists, actors, writers, pilots and entrepreneurs.

The other grand experiment in free education in this country, the Freedom Schools movement, also produced an amazing return on investment: in the 2012 Presidential election, voter participation rates were higher among African-Americans than whites. Take a moment to reflect on that. Not even fifty years ago, before the Voting Rights Act of 1965, African-Americans did not even have the right to vote. The thousands of young blacks that attended these schools for civic engagement and empowerment in 1964-65, and their children, are now at the forefront of what Peter Cooper called good citizenship.

If free education to WWII servicemen and to Mississippi black youth can produce such a massive return for society, let us envision what the same legislation could produce for all youth: from coast to coast, rich and poor alike, rural, urban, immigrant and non-immigrant.

This is the way out of the crippling debt that’s stalling our economy once more.

This is the way out of the ever-growing abyss separating the uber-wealthy and the permanently poor in America today, carving out separate sets of laws for Wall Street and for Main Street.

This is the way out of persistent unemployment and the mismatching of skills and available jobs that comes from the lack of access to higher education, an upside-down absolutely un-meritocratic system.

As I walk out of Greenwood Cemetery, I once again hear the thick Italian accent of the affable groundskeeper, whose name I now learn is also Pete. He’s moved on to discussing politics with the entrance guard, and they see me approach and ask if I found Peter Cooper. I answer in the affirmative, and Pete suggests that I bring the trustees of Cooper Union and the President himself over to see Cooper’s grave as well.

“I’ll suggest it to the students occupying his office,” I reply.

“They get it.”

Justin Wedes is an activist, educator, media-maker and community organizer. He’s the co-founder of the Paul Robeson Freedom School in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Its mission is to provide engaging, culturally-relevant curriculum to young adults in Brooklyn in order to train them to become educator-leaders in the struggle for high-quality, free education. To support the school, visit their website and join them on Friday, May 24th as they present “The World is my Home – The Life of Paul Robeson”.

More photos from the grave of Peter Cooper: